This post consists of a presentation which I gave to the staff at my school on cognitive load theory and retrieval practice. The whole session was two hours long and we only scratched the surface but it seem to go down well with the majority of teachers. You can download the workpack I used for the presentation here:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1L2j1l4hhjY55DkVounEfJ4UOLLuE5FKP01HFH3yJZdg/edit?usp=sharing

As always, comments and suggestions for improvement always welcome

Key words:

Working memory:

This is where thinking actually happens. It has a very finite capacity; it can only hold and process about four different items at a time. If it receives too much it fails.

Long-term memory:

Long-term memory has huge – almost infinite – capacity. It is here that we store our knowledge of facts and procedures. The goal is to stock our long-term memories with knowledge in a well organised, easily retrievable way and make recall of key aspects automatic. This frees up the working memory for new information.

Cognitive load:

This is the term used in cognitive science to describe how much capacity something takes up in the working memory. Cognitive overload is what happens if too many demands are placed on working memory at once

Phonological loop:

The part of the brain that deals with speaking, listening and reading.

The split-attention effect:

If pupils have to listen to someone talking at the same time as reading something on the board, then their attention is split – the spoken and the written information compete for attention.

Retrieval Practice:

The act of retrieving things from long-term memory

The Silent Teacher –

Example – Problem pair

Why silent?

To reduce cognitive load by not overloading the phonological loop.

It is a struggle to read and listen at the same time.

The split-attention effect:

If pupils have to listen to someone talking at the same time as reading something on the board, then their attention is split – the spoken and the written information compete for attention.

Silent Teacher Example Problem Pair – Name the steps (TLaC #21):

1. Split the white/blackboard in two (headed Worked Example and Your Turn)

2. On the left, the teacher works through an example. (In a primary context, this will usually involve using concrete or pictorial representations alongside abstract ones.)

3. After having explained this, children copy down this example into their books so that they can refer to it later and also practice setting it out correctly

4. On the right is a mathematically almost identical example for pupils to try themselves immediately after

5. The teacher then circulates to help anyone who is struggling

6. If the majority of the class is stuck, the teacher stops the class to unpick the misconception, but otherwise, children then go on to work through a series of very carefully chosen, structurally similar examples

7. The teacher does not stop and ask questions or check for understanding. Pupils watch and listen in silence

8. The teacher does not talk while modelling. Instead the teacher pauses briefly between each step, so pupils have a chance to think

9. Once the teacher has written the entire method on the board he or she can narrate what they have been doing.

Top Tips:

1. Present the information in written form first, and then explain it to avoid cognitive overload.

2. Words and pictures at the same time are fine, so bring out your concrete and pictorial examples.

Retrieval Practice

When we think about learning, we typically focus on getting information into students’ heads. What if, instead, we focus on getting information out of students’ heads?

Retrieval Practice Is Key In The Classroom

Retrieval practice is a strategy teachers can use to give pupils opportunities to have to try and remember things they have learnt previously; things they have begun to forget. Retrieval practice is quite simply giving children tasks where they have to try and retrieve an answer from their long-term memory. Each time pupils try and do this, that memory will become a bit stronger and a bit easier to find next time.

What is important for teachers to understand is that for the memory strengthening to happen, pupils must try to remember without any priming or reteaching from us. For retrieval practice to work, there has to be an element of struggle; it has to be at the very least, a bit hard to remember.

It works best when memories have been forgotten!

This ties into the Waldorf idea of “putting a topic to sleep” but is focussed on the “re-awakening” process which seems to be the important bit in terms of long term retention of content.

Retrieval in the Classroom

Becoming conscious of the power of Retrieval Practice as a learning strategy means we can make the best use of the brain’s natural recall functions.

Retrieval Practice solidifies knowledge in long-term memory:

Our memory is like a forest garden, not a hard drive – IE: we need to visit often and tend the garden.

Retrieval Practice also increases understanding:

Because students have a better understanding of classroom material by having practiced using this information, students can adapt their knowledge to new situations, novel questions, and related contexts.

Retrieval Practice helps us to identify gaps in learning:

In other words, not only does retrieval improve learning and help us figure out what students do know – more importantly, it helps us figure out what they don’t know. Teachers can adjust lesson plans to ensure common misconceptions are addressed and common gaps in knowledge are revisited if necessary.

TIPS:

It must be effortful for the student: The more difficult the retrieval practice, the better it is for long-term learning

It must involve the whole class

Feedback must be immediate

Keep it low-stakes

Techniques for implementing Retrieval Practice:

Low- (or no-) stakes quizzes

Multiple Choice questions – whole class

Exit Tickets (TLaC #26)

Mini-Whiteboards

Brain Dumps

Retrieval Grids

Retrieve-taking Vs note taking

Two Things

Think-Pair-Share

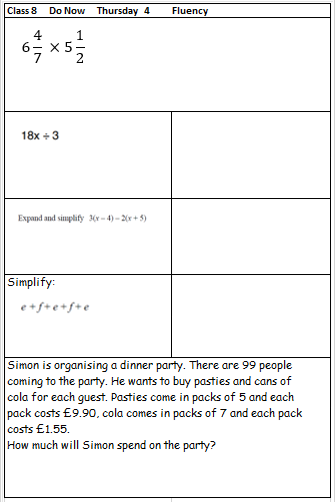

Example 1:

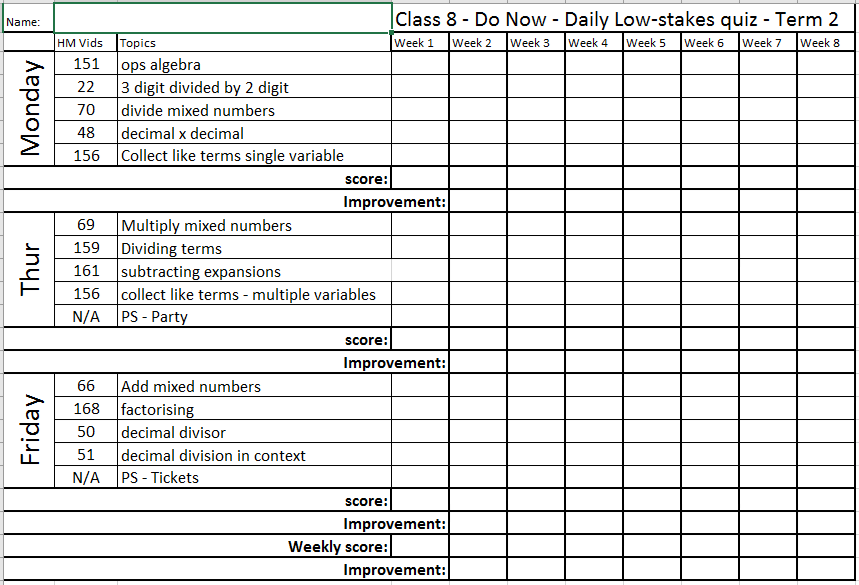

Low stakes quiz:

Low stakes quiz – record sheet:

Low Stakes Quiz (5-a-day) template:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1qUAnXHNa-hCS8yW0wJlSL2oaSJRkva8bmpWEQD86JI4/edit?usp=sharing

Example 2: Multiple-Choice Questions

Example 3: Mini-White boards

Taken from: https://ndhsblogspot.wordpress.com/2017/05/05/how-i-use-mwbs/

Why use them?

Despite the “faff factor”, mini whiteboards have a number of positive points:

- They help ensure that all students are thinking about and answering questions. You can immediately see who is joining in and who isn’t.

- You can use them to monitor who is ahead of the game, and find out which students are struggling.

- They allow you to draw out thoughts from quieter, less vocal students.

- You can check that everyone in the class is listening, following, understanding and applying ideas and concepts as they develop within a discussion.

And, possibly most importantly::

- They allow you to give students immediate (verbal) feedback based on their responses to a question.

How to use them:

This excellent blog post from @teacherhead is about practicing good teaching habits. One of the strategies mentioned was quizzing pupils using mini whiteboards. It suggests asking students to write answers down and then wait for a signal before showing them to you (simultaneously):

All-student response: using mini-whiteboards really well.

As I outline in this post – the No1 bit of classroom kit is a set of mini-whiteboards. The trick is to use them really well. You need to drill the class to use them seriously, to do the ‘show me’ action simultaneously in a crisp, prompt manner and, crucially, you need to get students to hold up the boards long enough for you to engage with their responses. Who is stuck? Who has got it right? Are there any interesting variations/ideas? Use the opportunity to ask ‘why did you say that? how did you know that?’ – and so on. It takes practice to make this technique work but it’s so good when done well. Taken from Ten teaching techniques to practise – deliberately.

Mini whiteboards are very useful when used effectively with a crisp “show-me” routine. MWBs are most effective if you question students further once they have answered a question.

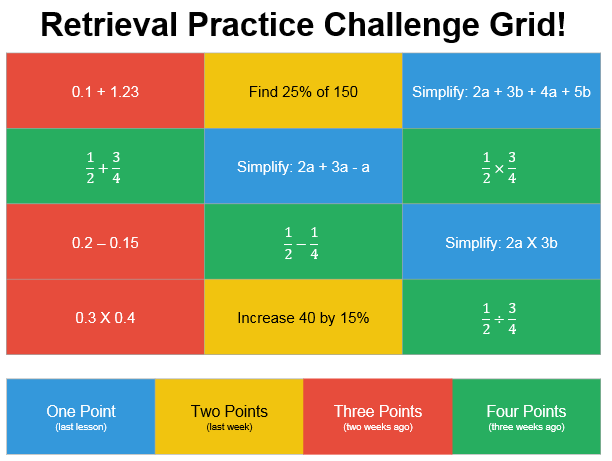

Example 4: Retrieval Grid

https://www.retrievalpractice.org/strategies/2018/9/28/retrieval-grids

ICTevangelist.com/retrieval-practice-challenge-grid-template

Sources:

Craig Barton’s “How I Wish I’d Taught Maths: Lessons learned from research, conversations with experts, and 12 years of mistakes”:

Clare Sealy: “How I Wish I’d Taught (primary) Maths” blog series:

https://thirdspacelearning.com/blog/clare-sealy-introduction-cognitive-load/

Doug Lemov: Teach Like a Champion 2.0

Roberto Trostli: MAIN LESSON BLOCK TEACHING IN THE WALDORF SCHOOL Questions and Considerations:

https://www.waldorflibrary.org/images/stories/articles/RB6107.pdf

RetrievalPractice.org

https://www.retrievalpractice.org/library

Brendan Bayew:

Craig Barton’s How I wish I’d Taught Maths – My Takeaways

Moving from No-Stakes to Low-Stakes

Resources:

Retrieve-taking:

https://www.retrievalpractice.org/strategies/2018/5/11/retrieve-taking

Two Things:

https://www.retrievalpractice.org/strategies/2018/two-things

Brain Dumps:

https://www.retrievalpractice.org/strategies/2017/free-recall

Retrieving:

https://www.retrievalpractice.org/strategies/2018/time

Think-Pair-Share:

https://www.retrievalpractice.org/strategies/2018/think-pair-share

Retrieval Grids:

https://www.retrievalpractice.org/strategies/2018/9/28/retrieval-grids

Multiple Choice Questions:

My Top Websites for Planning Lessons

Low Stakes Quiz (5-a-day) template

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1qUAnXHNa-hCS8yW0wJlSL2oaSJRkva8bmpWEQD86JI4/edit?usp=sharing

[…] https://hospitablewanderer.com/2018/12/28/cognitive-load-theory-and-retrieval-practice/ […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

LikeLike

[…] [I have written previously about Cognitive Load Theory and Retrieval Practice here] […]

LikeLike